A heatwave struck in the summer of 2016, so I made my holiday truly nordic: first, a trip to Norway across the polar circle and then cycling to a place where you can meet much fewer Czechs on vacation: the northeast of Poland.

Acclimatisation: Norway

First, I had to beat the obstacle named Norwegian Airlines, thanks to whom a few hours travel stretched into two full days, filled by additional programme like losing and searching for baggage or an unplanned “shortcut” over Tromso (at the very tip of Norway, you would have a hard time trying to devise a longer “shortcut”). But for a reward, I saw the Rago national park and the Lofoten. I also enjoyed many sunny days therexoticisme – measured by north-Norwegian standards – including some sunny midnights. And I can certify the Lofoten islands are really worth a visit. On the other hand, when I imagine the winter half of the year is just rain and darkness non-stop there, I really would not want to spend the whole year there…

The true exotics (for Czech tourists): Poland

Just to make sure no-one can say that I went to Poland to avoid the hills, I started going up the Giant Mountains of Krknoše (by train), from where I drove down to Poland, to Szklarska Poręba Poreba and Jelenia Góra. From there by night train and I woke up in Gdańsk, the real start of the journey. Departing from the historic Hanseatic city of Gdańsk, I crossed a pontoon bridge at Sobieszew, stopped on a sandy beach of the Baltic, and crossing over one of the many shoulders of Wisła I arrived to a rainy Malbork.

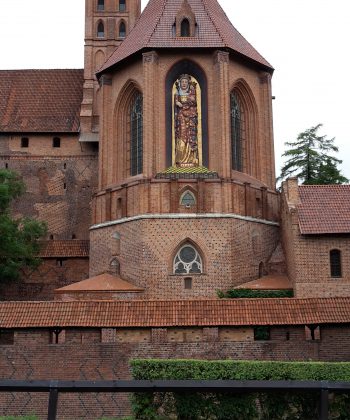

The Crusader castle of Malbork, the largest brick castle ever and, according to some measurements, the largest castle in the world (though Prague Castle is strangely recorded in the Guinness Book, having smaller total area), certainly did not disappoint by its sheer scale. It did disappoint a bit however by the interiors: at the end of the war, the Germans made it into their fortress, and after the Soviets had persuaded them to leave, there was not much of the castle left over. Most of it is reconstructed and not much of any original equipment was left.

By the way, during all the time I observed a few things where Polish countryside differs from the Czech one:

- Every proper village has at least one proper stork nest. And it’s not just in the north: when I crossed the to border to southern Poland during another trip, the first thing I saw was a stork.

- Plain brick houses and cathedrals are the trademarks of the north Poland; moving towards Belarus, these gradually turn into timber ones, and beyond Białystok some of the churches become eastern-orthodox.

- I expected worse roads than at home. But in fact they were probably better in the average, just more diverse: it is true that occasionally one encounters an official road that is nothing more than packed sand (and then one also faces the machine that takes up the full width of the road, regularly compressing the sand). But then, in the middle of a field, the sand road turns into a smooth all-new tarmac, funded by the EU. Why is no-one able to build such new roads in our countryside, if the access to EU funding should be the same?

I stopped in Frombork at the coast of the Vistula Lagoon, separated from the Baltic by the Vistula Spit. Besides seeing the cathedral, I had an excellent fish in a local pier pub, fresh from the sea for a price that would not pay for fish fingers at home. Then I turned east, towards the Masurian lakes. On my way there I passed one of the many German bunker areas around (just a short distance away is Hitler’s main Wolfschanze bunker, but unlike that one these bunkers in Mamerky are quite intact). The Masurian lakes made me think that next time I shall rather reserve a trip on one of the many yachts…

Then the landscape turned into a regular pattern: more lakes, another bunker (this time Himmler’s), a lake, a large Baroque fortress of Boyen (guarding the only way between two lakes), more lakes and finally, already beyond the Masurian tourist area, late in the evening I stumbled upon the largest bunkers compound: surprisingly preserved and freely accessible underground fortification from the first World War in Osowiec, complete with twenty-meter cannon shot craters. Before I was even able to see the full scale of the fortress the night arrived, so only a small part can be seen in the pictures.

Via Białystok and round the Siemjanowskie lake I arrived to a true primeval forest (Puszcza Białowieska). Although only the core part appears truly “primeval”, a larger area resembles just an old commercial forest. This forest is the last place where you can meet free-roaming European bisons – they even have their own traffic sign here. I only stumbled upon them in the corral, so rather than the bisons it was the Belarusian border that ultimately stopped me.

I hit the border once more around Bobrówka, but then I already turned around, crossed the Bug river (a ferry for 2+ cars but yet a 100% ecological propulsion – a hard-core ferryman and his iron bar), and passing the place where some of the first rockets ever reached the universe (V2), only to result into this German top secret being divulged to London by local Polish partisans, I arrived in Warsaw. I already knew the modern part of Warsaw (not so impressed by that part), but for the first time I had a chance to see the historical part. And that one indeed did impress me, considering that what seems to be a historical city center, was actually all rebuilt from scratch by the Poles after the war. By the end of the war there were just low hundreds of last survivors in the entire city of Warsaw and around 90% of buildings were razed to the ground.

From Warszawa I took a train straight home. A lesson for the next time: if I got off the train just before the border and boarded it again just behind the border, it might be 5x cheaper.

Cześć rowerzystom!